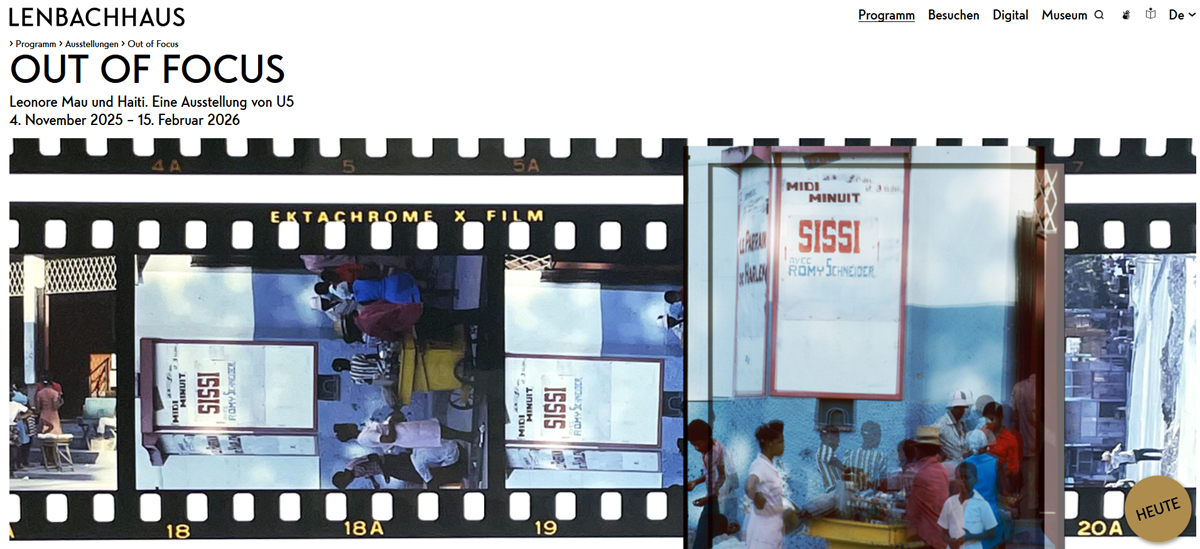

Quelle: https://visual-history.de/2026/02/05/out-of-focus-leonore-mau-und-haiti/

Roma and Sinti darstellen

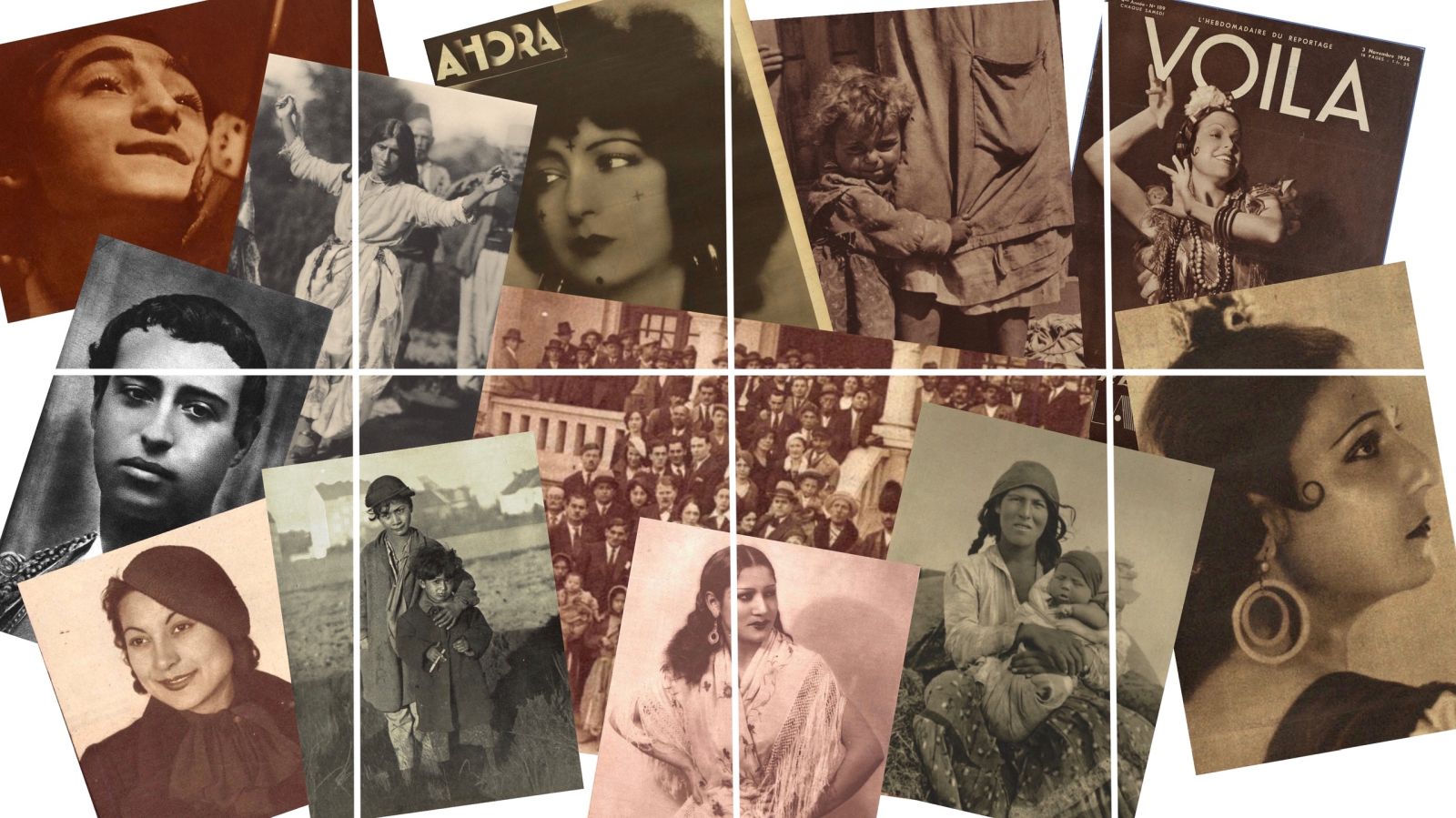

Quelle: https://visual-history.de/2025/11/11/holzer-roma-and-sinti-darstellen/

Reimagining One’s Own. Ethnographic Photography in Nineteenth- and Early-Twentieth-Century Europe

Inv.-Nr. pos/774 in der Fotosammlung des Volkskundemuseum Wien ©

The photo collection of the Volkskundemuseum Wien was established along the lines of a “comparative ethnology of Europe” in the late nineteenth century, focusing on the territories of the Habsburg Monarchy. Today, the assembled materials raise manifold questions about their origins and, as a consequence, about the visual ethnography of “one’s own”.

Just as colonial ethnography created an image of the “others,” ethnographers and folklorists in Europe approached their “own” populations within the continent. The work here is always asymmetrical; it was the ethnographers and photographers who determined what the image of those studied by them looked like. Ethnography at the time conceived “people” with a respective essence in mind. It designed primitivizing and exoticizing typologies, such as in the form of so-called type photography—a genre of images that circulated far beyond the narrow scientific context and could serve the most diverse purposes.

[...]

Freiwilligkeit und Zwang

Im Zuge von Handelsreisen, Verwaltungstätigkeiten und Forschungsexpeditionen entstanden bis zur Mitte des 20. Jahrhunderts zahlreiche Fotografien in kolonialistisch-eurozentrischen Kontexten,[1] die das Leben der Bewohner*innen der bereisten Gebiete „als Fremdbilder […] vermittelt durch die vielfältigen Mechanismen der Distribution und des Konsums“[2] darstellten. Manche bilden eindeutig erkennbar inszenierte Szenen wie Gruppenporträts, Kampfgeschehen oder arrangierte Studioaufnahmen ab, andere hingegen suggerieren, dass die Fotografien spontan im Feld aufgenommen wurden. Sie umfassen auch standardisierte anthropometrische Aufnahmen, sogenannte Typenfotografien,[3] welche die abgebildeten Personen häufig nackt oder in vermeintlich traditionellen Gewändern zeigen und wiederum als Wissensquelle für Forscher*innen zur Identifizierung von Gruppen dienten.

Vielfach galten die Abgebildeten dabei als Gegenbild zur westlichen Zivilisation. So stellt der Historiker Jens Jäger fest: „Ob es sich nun um Bilder von Einwohnern der europäischen Kolonien handelte, um Aufnahmen von Bauern, Arbeitern und Angehörigen der Unterschichten oder um Bilder von bürgerlichen Männern und Frauen, implizit wurden diese in der ‚westlichen‘ Kultur an der Norm des weißen, bürgerlichen Menschen (vor allem des Mannes) gemessen.“[4]

Der überwiegende Teil der Bilder, die in einem im weitesten Sinne ethnologischen Forschungskontext aufgenommen und überliefert worden sind, wurde zudem nicht von den Einheimischen erstellt. Sie bilden Machtverhältnisse mal ganz offen, mal verdeckter ab.

[...]

Zeigen / Nichtzeigen

Screenshot der Website der Universitätsbibliothek der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin: Ethnologie (Volks- und Völkerkunde) [15.09.2020]

Sollen Bilder aus solchen Kontexten, oftmals nach Jens Jäger der Reisefotografie oder dem anthropologischen und ethnografischen Stil der Wissenschaftsfotografie zuzuordnen,[3] frei zugänglich im Internet gezeigt oder sollte dies lieber unterlassen werden?

[...]

Neun Blicke auf ethnografische Bilderwelten

Ein Bild verwundert in einer Ausstellung mit dem Titel „Fragende Blicke. Neun Zugänge zu ethnografischen Fotografien“: Die Farbaufnahme im klassischen 10 x 15 cm-Format aus dem Jahr 1984 zeigt drei Personen, die vor dem Museum Fünf Kontinente (damals Staatliches Museum für Völkerkunde) in der Münchner Maximilianstraße posieren. Es scheint ein grauer, kalter Tag gewesen zu sein, an dem die Aufnahme entstand, die in ihrem Stil an Touristenaufnahmen erinnert und sich in jedem privaten Familienfotoalbum befinden könnte. Zwischen einer Frau rechts und einem älteren Herrn links steht ein junger dunkelhäutiger Mann. Durch die Bildunterschrift „Alfredo (Aherowë) zu Besuch in München“ kann schließlich eine Verbindung zu einer daneben hängenden Aufnahme mit dem Titel „Yaima, Asiawës Frau, mit ihrem Sohn“ hergestellt werden. Sie wurde 1954, also 30 Jahre zuvor, im Dorf Mahekodotedi in Venezuela, in dem Waika, eine Gruppe der Yanomami leben, von dem älteren Mann auf der Farbaufnahme, dem Ethnologen Otto Zerries aufgenommen. Auf dem Bild sehen wir eben jenen jungen Mann als Baby auf dem Rücken seiner Mutter.

Fragende Blicke. Bild 01: Junge Frau mit Kind im Tragetuch, Yamolemi mit Nichte Liehemi (das oben im Text beschriebene Bild ist als Pressefoto nicht zugänglich).

[...]

Quelle: https://www.visual-history.de/2019/04/01/neun-blicke-auf-ethnografische-bilderwelten/

„Wissenschaftlicher Tourismus“ im Age of Empire

Archiv-August #7: Indigene und Eisenbahnen, Ruinen und Metropolen

Archiv-August #7: Der siebte Beitrag unserer Reihe erschien erstmals am 07. Dezember 2015. Viel Spaß beim Lesen!

Das Wissen von Europäern um Südamerika ist seit der frühen Neuzeit, als der Kontinent Ziel der europäischen Expansion wurde, durch Bilder vermittelt worden.[1] Diese Bildüberlieferung erhielt im 19. und frühen 20. Jahrhundert neue Impulse: Fotos und später Bildpostkarten zeigten den Menschen im Deutschen Reich ein ambivalentes Bild des fremden Kontinents, das mit bestehenden Vorstellungen und Projektionen zusammenwirkte, aber auch mit diesen konkurrierte. Die Ambivalenz des Südamerikabildes wird deutlich in den Motiven, denn die Bildmedien zeigten einerseits Eisenbahnen und Bahnhöfe, Stadtansichten, repräsentative Gebäude, Häfen, Zoos und Fabriken.

[...]

Quelle: https://visual-history.de/2021/08/30/indigene-und-eisenbahnen-ruinen-und-metropolen/

Was macht den Menschen aus?

ARCHIV-AUGUST 2022

Die Visual History-Redaktion nutzt den Monat August, um interessante, kluge und nachdenkenswerte Beiträge aus dem Visual History-Archiv in Erinnerung zu rufen. Für die Sommerlektüre haben wir eine Auswahl von acht Artikeln getroffen – zum Neulesen und Wiederentdecken!

(5) Vielleicht plant ja die eine oder der andere eine Urlaubsreise nach Luxemburg. Unbedingt zu empfehlen ist dabei der Besuch von Château Clervaux. Seit 1994 beherbergt es die „Family of Man“-Ausstellung, die 1955 im Museum of Modern Art in New York Premiere feierte, in den folgenden sieben Jahren durch die ganze Welt reiste und in 150 Museen gezeigt wurde. Edward Steichen, damaliger Leiter der Fotoabteilung des MoMA und Kurator der Ausstellung sowie gebürtiger Luxemburger, hatte sich für die permanente Installation im Château Clervaux ausgesprochen. Sein Anliegen war es, in der Nachkriegsära und der Zeit des Kalten Kriegs mittels Fotografien „dem Menschen die Menschheit zu erklären“.

[...]

Quelle: https://visual-history.de/2022/08/22/was-macht-den-menschen-aus/

Wenn Bilder plötzlich lächeln

Die Fotografie als scheinbar objektive Darstellungsform gewann im 19. Jahrhundert sowohl qualitativ als auch quantitativ rapide an Bedeutung. Dabei erschien das Medium auch als optimal, um Informationen über andere Kulturen und Völker zugänglich zu machen. Das Ethnologische Museum Berlin-Dahlem besitzt eine stattliche Sammlung entsprechender Aufnahmen von Forschungsreisenden aus zahlreichen Nachlässen, Ankäufen oder Schenkungen. Allein aus Lateinamerika befinden sich über 6000 Stück – entstanden zwischen 1868 und den 1930er-Jahren – in der Sammlung.

„Fotografien berühren“ lautet der Titel der aktuellen Ausstellung in Dahlem, die sich zum Ziel gesetzt hat, eben jene Fotografien aus Lateinamerika neu zu erschließen und dabei nicht die Forschungsreisenden oder Entdeckungen in den Fokus zu rücken, sondern die Abgebildeten.

Die Präsentation entstand in Kooperation des Ethnologischen Museums mit dem Museum für Asiatische Kunst in Berlin-Dahlem und ist Teil der dritten sogenannten Probebühne des Humboldt Lab. In Vorbereitung auf den Umzug der beiden Museen und ihrer Sammlungen in das im Bau befindliche Berliner Stadtschloss experimentieren Kuratoren und Gestalter mit neuen Ausstellungsformen, die vor allem neue Perspektiven auf die Sammlungen ermöglichen sollen.

[...]

Quelle: https://www.visual-history.de/2013/12/12/wenn-bilder-ploetzlich-laecheln/